O'odham

Winter Stories 2013

By Roy Cook, Opata Oodham edit

On cold winter nights, grandparents and other elders tell stories to pass

on the values of our people. Traditionally, O'odham parents have always

thought ahead to their children's futures, even when this meant speaking

English at home so that children could succeed in school. It is for each

of us to keep the stories alive Today, however, most of the old stories

are written and illustrated in books because the storytelling tradition

has weakened. Not many elders know the stories from their family or area.

But we can read and share related or remembered story traditions. It is

most important to replant the seeds of respect for the oral tradition

and appreciation of traditional culture.

In the Southwest there are some shared story telling traditions. For Hopi

poet Ramson Lomatewama, the winter solstice represents more than an astronomical

event. Its meaning extends beyond its ancient impact on the sowing of

crops and management of winter reserves. This is a sacred time, "filled

with mystery and power, because this is a time of reverence and respect

for the spirits," he told Arizona

Public Radio on January 10, 2002.

On the show, he discusses

how the new winter moon signals the Winter solstice and the beginning

of the storytelling season:

"The dogs work me up early. As I got out of bed to let them out,

I noticed that the moon was just a thin crescent. Experience told me that

the season known as kyaamuya would soon begin. Kyaamuya is filled with

mystery and power, because this is a time of reverence and respect for

the spirits. We're taught to be mindful of certain taboos. Even today

I tried to head those instructions. I don.t cut my hair or dig holes.

Even today, I try not to wander outside after dark, and I don't whistle,

make loud noises or beat on drums.

I remember going back to the reservation this time of year and spending

weekends at my grandmothers. A wood stove kept us warm. We had an old

lantern that hissed and had a soft light. None of us kids dared to go

outside when it got dark because it was kyaamuya and spirits were wandering

out there. But kyaamuya was also the time for storytelling. I remember

those nights when old men came to visit. Some of them I recognized as

family; others I didn't know. They'd eat supper with us, but well before

the table was cleared, someone would ask if they could stay and tell stories.

And we always passed around a yucca sifter basket filled with kutuki,

the Hopi version of popcorn. Some of the stories were long and could take

hours and some of the stories were short."

Traditional O'odham

stories vary from village to village according to Grace Palacios who grew

up in South Komelik, a village just north of the U.S./Mexico border.

This

version of the Milky Way story she remembers features Coyote, a trickster

who doesn't listen well and always ends up in trouble.

This

version of the Milky Way story she remembers features Coyote, a trickster

who doesn't listen well and always ends up in trouble.

One day, Coyote was playing in someone's kitchen among the cooking

utensils. He was trying to find some food to eat, but then he heard someone

coming. He grabbed the first thing he saw, which was a bag of flour, and

ran. He thought the best way to escape was by going into the sky. As he

ran into the sky, the bag tore open. The flour flew everywhere, creating

the Milky Way galaxy.

"The Milky Way galaxy is a trace of what Coyote shouldn't have been

doing," Palacios said. "Not to mention, it gives me insight

of how my people made sense of their surroundings."

Long ago, the elders in each O'odham family told traditional stories to

their children and grandchildren. For the youngsters, it was considered

story time, said Lois Liston, a Tohono O'odham traditional arts teacher

at Ha:san Preparatory and Leadership School in Tucson. Ha:san is a bicultural

public high school designed for Native youths interested in attending

college.

The stories were told during winter because of the long nights and for

safety reasons. The O'odham believe they can talk about dangerous animals,

such as bears and snakes, when they're hibernating and can't harm anyone,

Liston said. Keep stories alive

Today,

however, most of the old stories are written and illustrated in books

because the storytelling tradition has weakened. Not many elders know

the stories from their family or area, Liston said. One of her jobs as

a traditional arts teacher is to strengthen her students. cultural knowledge

by telling them the old stories. "I like telling traditional stories

to students because there are so many different versions," Liston

said. "When I share stories, I always tell them, 'This is how it

was told to me."

Today,

however, most of the old stories are written and illustrated in books

because the storytelling tradition has weakened. Not many elders know

the stories from their family or area, Liston said. One of her jobs as

a traditional arts teacher is to strengthen her students. cultural knowledge

by telling them the old stories. "I like telling traditional stories

to students because there are so many different versions," Liston

said. "When I share stories, I always tell them, 'This is how it

was told to me."

Another version of

the Milky Way story, for example, has Coyote spilling cornmeal to form

the stars. In another variation, Coyote steals a bag of white tepary beans

and scatters them while trying to escape, said Ron Geronimo, a Tohono

O'odham language teacher at Tohono O'odham Community College in Sells.

Yet another story describes an old man and a young boy. An old man was mean to his grandson, so the boy decided to leave and went up into the sky. The grandson lay in the sky and could see his grandfather down below. The grandfather could not find his grandson and began to feel badly about how he had treated him. The old man walked around crying as he looked for the boy. After time had passed, the grandson also began to feel badly and decided to come back down to give his grandfather a way to be with him. The boy told his grandfather that he had left because the old man was mean to him, and so he had made a new home in the sky. The boy gave his grandfather some seeds and told him to plant them. In four years, the old man would have enough seeds so he would never go hungry. The grandson also told his grandfather the seeds were white tepary beans. The gray streak above in the sky was made of these beans, and this was his home. He told his grandfather that whenever the old man missed him, he could look up and see him across the sky.

Each traditional

story carries a deeper meaning. "The importance of any story is what

it is trying to teach you," Geronimo said. "In this story it

is trying to teach us about how we should treat people and each other.

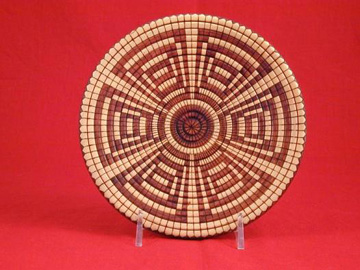

"Stories and baskets have traditionally played a large part in the

social and economic culture of the Tohono O'odham tribe. Aspects of traditional

stories often are woven into the designs of the Tohono O'odham baskets.

Mostly, baskets were very important in the everyday life of the tribe.

It was the women's achievement and artistic expression in the tribe to

weave the baskets. The baskets were used to haul grain and food. Many

baskets were woven so tightly that they could hold water and liquor. Baskets

were also very important in ceremonies, such as the Saguaro wine Rain

Ceremony.

What

makes the Tohono O'odham basket so uniquely beautiful is their style of

weaving. The Tohono O'odham tribe has one of the most beautiful styles

of basket weaving. The tight coiled basket and amazing designs make their

baskets so appealing. Some of the baskets are woven so tight that they

are used to hold water and other liquids. A few tribe members believe

that the ancient baskets are of better quality than those that are made

today. Curators at the University of Arizona State Museum looking at ancient

baskets retrieved during archaeological digs admire the workmanship and

learn prehistoric designs and patterns. Many of the old baskets are made

with splits of willow branches that are typically hard to work with. Most

Tohono O'odham weavers today use primarily yucca, bear grass, and devils

claw. The designs in the baskets are not made with any dyes. All of the

baskets are made of natural colors. The white stitches in the baskets

are yucca and the coil is shredded bear grass. The black is from devils

claw, the rusty red is from the root of the yucca plant, and the green

is from yucca leaves.

What

makes the Tohono O'odham basket so uniquely beautiful is their style of

weaving. The Tohono O'odham tribe has one of the most beautiful styles

of basket weaving. The tight coiled basket and amazing designs make their

baskets so appealing. Some of the baskets are woven so tight that they

are used to hold water and other liquids. A few tribe members believe

that the ancient baskets are of better quality than those that are made

today. Curators at the University of Arizona State Museum looking at ancient

baskets retrieved during archaeological digs admire the workmanship and

learn prehistoric designs and patterns. Many of the old baskets are made

with splits of willow branches that are typically hard to work with. Most

Tohono O'odham weavers today use primarily yucca, bear grass, and devils

claw. The designs in the baskets are not made with any dyes. All of the

baskets are made of natural colors. The white stitches in the baskets

are yucca and the coil is shredded bear grass. The black is from devils

claw, the rusty red is from the root of the yucca plant, and the green

is from yucca leaves.

It has become harder for the Tohono O'odham tribe to gather the necessary

materials for basket weaving. Today tribal members have to travel many

miles to gather material for basket weaving, but it is important to the

identity of the tribe, so the tradition, although more difficult has been

maintained. In the ancient weaving of the Tohono O'odham the basic material

for basketry weaving could be collected with little effort, even though

many elements ripened or were unusable during different seasons. There

is little open land to the public and so much development of land that

it is getting more and more difficult to find the material needed to make

baskets. Some Materials, such as, devil's claw are now being cultivated

in a community garden in Sells, Arizona.

Basket

weaving for the Tohono O'odham has gone from an essential part of life

to a hobby. In ancient times, baskets were used every day for holding

food, gathering food, holding water and for ceremonial use. As time went

on and modern inventions came into tribal life, basket weaving became

a hobby for many people and a way to keep the tradition alive. Baskets

were sold for very little money and used by people for common things like

trashcans. Then people began to realize the art that went into basket

weaving.

Basket

weaving for the Tohono O'odham has gone from an essential part of life

to a hobby. In ancient times, baskets were used every day for holding

food, gathering food, holding water and for ceremonial use. As time went

on and modern inventions came into tribal life, basket weaving became

a hobby for many people and a way to keep the tradition alive. Baskets

were sold for very little money and used by people for common things like

trashcans. Then people began to realize the art that went into basket

weaving.  Simple

baskets took hours and hours of work, both for the weaving and the collection

of the weaving materials. People from all over the United States still

go to the Tohono O'odham reservation to buy baskets for very little money

and then sell them for hundreds and sometimes thousands of dollars, to

people all around the country.

Simple

baskets took hours and hours of work, both for the weaving and the collection

of the weaving materials. People from all over the United States still

go to the Tohono O'odham reservation to buy baskets for very little money

and then sell them for hundreds and sometimes thousands of dollars, to

people all around the country.

When the O'odham tribe realized how much their baskets were selling for

they decided to market the baskets themselves, cutting out the middleman.

As a result, sales are the main reason for weaving nowadays, though some

baskets still have traditional uses.

There

is no one meaning to the Man in the Maze. Interpretations of the image

vary from family to family. A common interpretation is as follows: The

human figure stands for the O'odham people. The maze represents the difficult

journey toward finding deeper meaning in life. The twists and turns refer

to struggles and lessons learned along the way. At the center of the maze

is a circle, which stands for death, and for becoming one with Elder Brother

I'itoi, the Creator. Other O'odham see the image of a man as representative

of an individual, or all of mankind, or I'itoi himself.

There

is no one meaning to the Man in the Maze. Interpretations of the image

vary from family to family. A common interpretation is as follows: The

human figure stands for the O'odham people. The maze represents the difficult

journey toward finding deeper meaning in life. The twists and turns refer

to struggles and lessons learned along the way. At the center of the maze

is a circle, which stands for death, and for becoming one with Elder Brother

I'itoi, the Creator. Other O'odham see the image of a man as representative

of an individual, or all of mankind, or I'itoi himself.

Storytelling helps connect the O'odham people to their landscape. There

are stories about the sky, the weather, the mountains, saguaros and desert

animals. It is this landscape that makes them Desert People, Palacios

said. Stories remind her of her ancestors and make the connection with

the past more tangible. O'odham stories show that everything has a purpose.

They also help establish values and boundaries that teach O'odham people

how to live their life." Liston said, "The importance of the

stories is to give directions and guidance to the younger generation on

how to live as a Tohono O'odham, The stories also remind us of our heritage

and culture and the responsibilities we have to one another."

Today, we as a Nation need to return to a view that puts learning at the

center of childhood. Studying at school, learning through play and family

life-this is the work of childhood. In the same way that learning is central

to childhood; traditional education is a key to our Tribal Nation's success.

Nationwide, studies have proven that western higher education brings higher

income, lower unemployment, and better health for individuals, and higher

tax revenues, lower crime rates, and improved civic life for the total

American community.

Hoping for a Happy, Healthy, and Holiday for all our Families. Ho'ige

idalig.